The first military unit raised on the Australian mainland appeared in September 1800, when Governor Hunter asked 100 free male settlers in Sydney and Parramatta to form Loyal Associations (English volunteer units raised to put down civil unrest) and practice military drill in case the Irish convicts rebelled. Six years later Governor King recruited six ex-convicts as the nucleus of a military bodyguard, creating the first full-time military unit to be raised in Australia. Both these groups joined British regulars in suppressing the Castle Hill uprising.

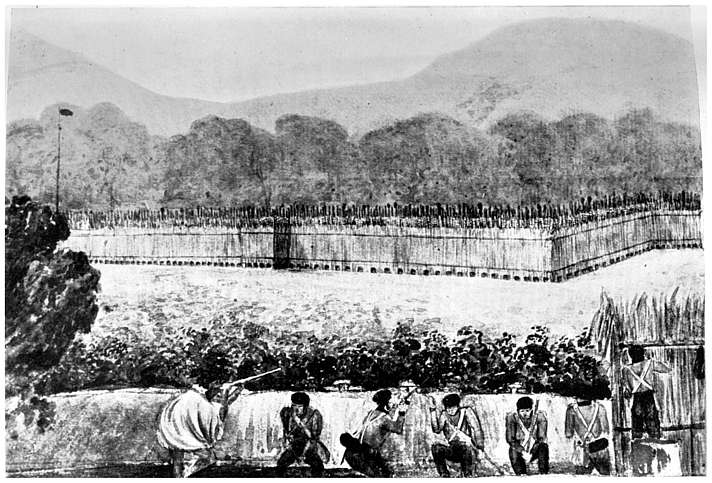

Anglo-Maori wars

of the 1840s and 1860s

Resulting from the continuing expansion of European settlers onto Maori land and the colonial government’s determination to crush native independence, the first war took place in 1845?6. With insufficient troops in New Zealand to meet the threat, the 58th Regiment of Foot, then based in Australia, was dispatched in February 1845, soon to be followed by further troops. Fighting died down after 1846 but flared again in 1860 before a truce was declared and peace returned.

By 1863 hostilities had reignited, and New Zealand’s colonial authorities requested further assistance from Australia. A contingent of British troops was dispatched, along with the Victorian Colonial steam corvette, Victoria. In July 1863 British troops invaded the Waikato area and news of the continuing campaign spread through the Australian colonies. Some 2,500 volunteers offered their services on the promise of settlement on confiscated Maori land by New Zealand recruiters; most joined the Waikato Militia regiments, others became scouts and bush guerrillas in the Company of Forest Rangers. Few of these volunteers were involved in major battles, and fewer than 20 were killed.

Sudan

1885 (New South Wales Contingent)

In the early 1880s the British-backed Egyptian regime in the Sudan was threatened by an indigenous rebellion under the leadership of Muhammed Ahmed, known to his followers as the Mahdi. In 1883 the Egyptian government, with British acquiescence, sent an army south to crush the revolt. Instead of destroying the Mahdi’s forces, the Egyptians were soundly defeated, leaving their government with the problem of extricating the survivors. The difficulties of evacuating their forces in the face of a hostile enemy quickly became apparent, and the British were persuaded to send General Charles Gordon, already a figure of heroic proportions in England, to consider the means by which the Egyptian troops could be safely withdrawn.

Disregarding his instructions, Gordon sought instead to delay the evacuation and defeat the Mahdi; like the Egyptians, Gordon failed and found himself besieged in Khartoum. The popular general’s predicament stirred public opinion in England, leading to demands for an expeditionary force to be dispatched to his rescue. The relief force was sent from Cairo in September 1884, but it was still fighting its way up the Nile when Gordon was killed in late January the following year. Gordon’s exploits were well known throughout the British Empire, and when the telegraph brought word of his death to New South Wales in February 1885 it was met with recriminations against the Liberal government led by William Gladstone for having failed to act in time.

With news of Gordon’s death and the Canadian government’s offer of troops for the Sudan, the NSW government cabled London with its own offer. To make its proposal more attractive, it offered to meet the contingent’s expenses; London accepted but stipulated that the contingent would be under British command. Similar offers from the other Australian colonies were declined.

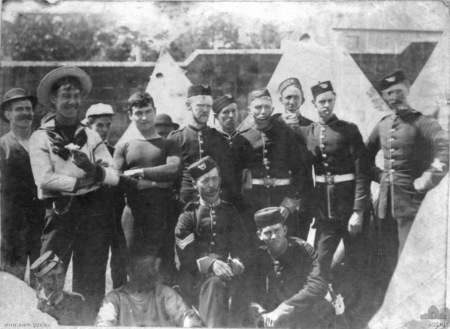

The British government’s acceptance of the contingent was received with enthusiasm by the NSW government and members of the armed forces; it was seen as a historic occasion, marking the first time that soldiers in the pay of a self-governing Australian colony were to fight in an imperial war. The contingent, an infantry battalion of 522 men and 24 officers and an artillery battery of 212 men, was ready to sail on 3 March 1885. It left Sydney amid much public fanfare, generated in part by the holiday declared to farewell the troops; the send-off was described as the most festive occasion in the colony’s history. Support was not, however, universal, and many viewed the proceedings with indifference or even hostility. The nationalist Bulletin ridiculed the contingent both before and after its return. Meetings intended to launch a patriotic fund and endorse the government’s action were poorly attended in many working-class suburbs, and many of those who turned up voted against the fund. In some country centres there was a significant anti-war response, while miners in rural districts were said to be in “fierce opposition”.

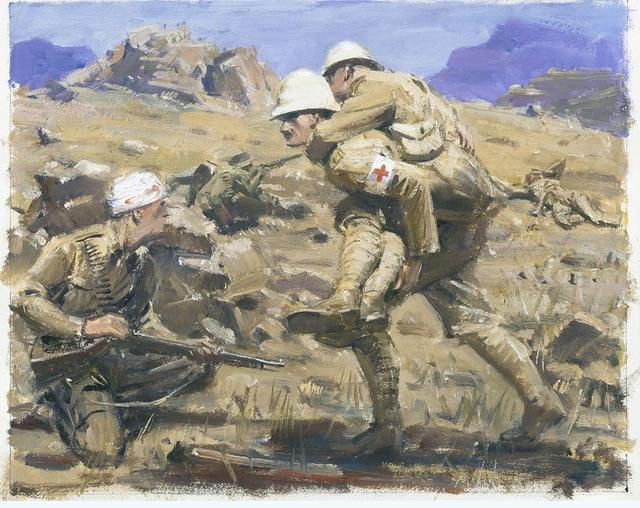

The NSW contingent anchored at Suakin, Sudan’s Red Sea port, on 29 March 1885 and were attached to a brigade composed of Scots, Grenadiers and Coldstream Guards. Shortly after their arrival they marched as part of a large “square” formation – on this occasion made up of 10,000 men – for Tamai, a village some 30 kilometres inland. Although the march was marked only by minor skirmishing, the men saw something of the reality of war as they halted among the dead from a battle which had taken place eleven days before. Further minor skirmishing took place on the next day’s march, but the Australians, now at the rear of the square, sustained only three casualties, none fatal. The infantry reached Tamai, burned whatever huts were standing and returned to Suakin.

After Tamai, the greater part of the NSW contingent worked on the railway line which was being laid across the desert towards the inland town of Berber on the Nile, half-way between Suakin and Khartoum. Far from the excitement they had imagined, the Australians suffered mostly from the enforced idleness of guard duties. When a camel corps was raised, fifty men volunteered immediately. On 6 May they rode on a reconnaissance to Takdul, 28 kilometres from Suakin, again hoping for an encounter with the Sudanese, but the only action that day involved two newspaper correspondents who had accompanied the patrol before leaving the cameleers to file their stories in Suakin. They soon found themselves surrounded by enemy forces, and one was wounded as they fled. The camel corps made only one more sortie – on 15 May, to bury the bodies of men killed in fighting the previous March.

The artillery saw even less action than the infantry. They were posted to Handoub where, having no enemy close enough to engage, they drilled for a month. On 15 May they rejoined the camp at Suakin. Not having participated in any battles, Australian casualties were few: those who died fell to disease rather than enemy action. By May 1885 the British government had decided to abandon the campaign and left only a garrison in Suakin. The Australian contingent sailed for home on 17 May 1885.

The contingent arrived in Sydney on 19 June. They were expecting to land at Port Jackson and were surprised to disembark at the quarantine station on North Head near Manly as a precaution against disease. One man died of typhoid there before the contingent was released. Five days after their arrival in Sydney the contingent, dressed in their khaki uniforms, marched through the city to a reception at Victoria Barracks where they stood in pouring rain as a number of public figures, including the Governor, Lord Loftus, the Premier, and the commandant of the contingent, Colonel Richardson, gave speeches. It was generally agreed at the time that, no matter how small the military significance of the Australian contribution to the adventure, it marked an important stage in the development of colonial self-confidence and was proof of the enduring link with Britain.

Boer War

1889–1902

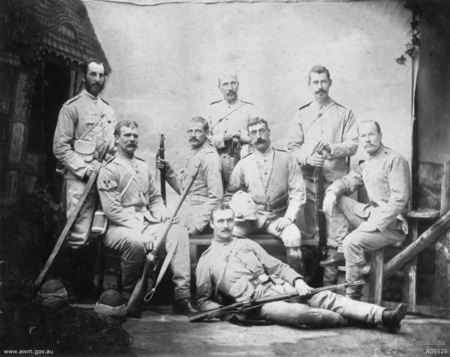

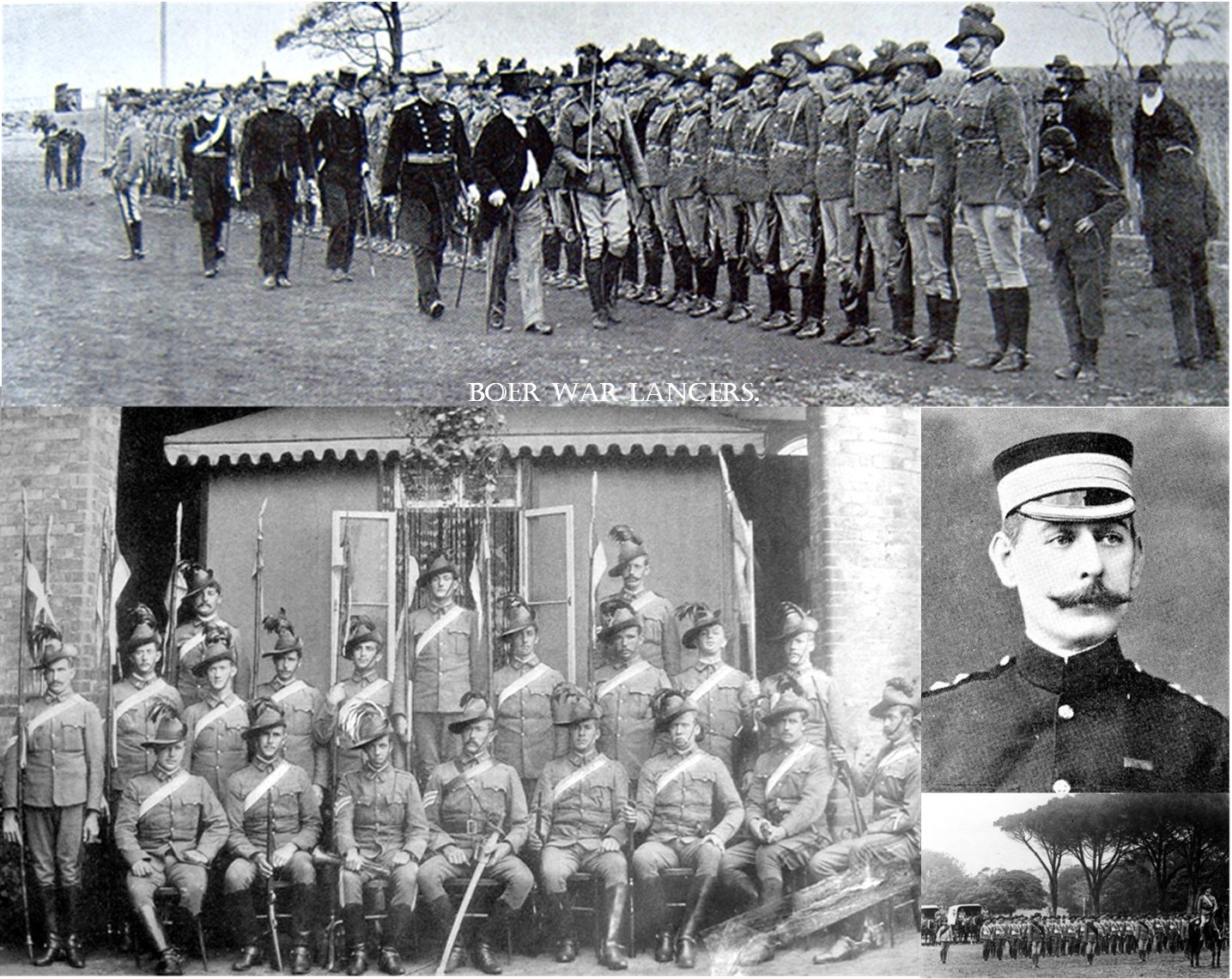

From 10th October 1899 to the end of May 1902 a bitter conflict raged across the South African veldt between Britain and her Empire and the two largely self governing Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. The six Australian States (colonies) were quick to make troops available to Britain when a Boer ultimatum to the British expired Boer commandos streamed across the borders into the British colonies of the Cape of Good Hope and Natal. The first formed unit of troops from Australia, a squadron of the New South Wales Lancers landed in Capetown on 2 November 1899, less that one month after hostilities began.

Up until 1899 for Australians there had been quite fierce fighting in some areas as European settlement expanded across the lands of the Aboriginal peoples, and two minor rebellions on the Australian mainland quickly put down by British garrison troops. Australians had also fought in the Maori wars in New Zealand and, in 1885, New South Wales sent a 700 strong contingent of infantry and artillery, with a small medical detachment, to the Sudan in North Africa. The Boer War was the first full commitment of troops by all the Australian Colonies to a foreign war and with the formation of the Australian Commonwealth on 1st January 1901 it became our country’s first military involvement as a nation.

Australia’s contribution was significant; we suffered casualty numbers which have only been exceeded by those of World Wars 1 and 2. In all, over 16,000 troops were engaged in the Australian contingents and another 7,000 Australians fought in other colonial and irregular units. Possibly 1,000 Australians lost their lives on service in South Africa during the Boer War.

In the beginning there was a preference for infantry units but the value of Australian horsemen was quickly recognized as mounted infantry, due to their capacity to deploy quickly and their ability to match the Boers’ own game. Therefore they were much sought after. With the exception of one field artillery battery and some medical groups (field ambulance, stretcher bearers and some 60 nurses) the Australian forces in South Africa comprised mounted infantry. Along with the New Zealanders, Australian horsemen were unsurpassed as scouts and were greatly valued by column commanders. After Federation the mounted troops which were sent to South Africa included the various Australian Commonwealth Horse units.

Our soldiers, who were truly the first Australian expeditionary force to fight overseas, did Australia proud in the Boer War as they have done in all conflicts since. Informed military commentators saw the magnificent defence of Elands River by Australian and Rhodesian troops as the finest episode of the whole war. The majority of the defenders were Australian bushmen, mainly men from Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria with a lesser number from Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania. They manfully defended the post against impossible odds for 12 days.

China

(Boxer Rebellion), 1900-01

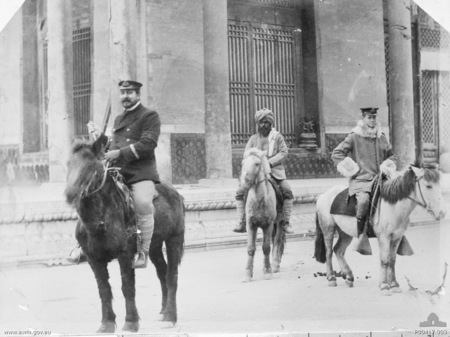

Australian colonies were keen to offer material support to Britain. With the bulk of forces engaged in South Africa, they looked to their naval contingents to provide a pool of professional, full-time crews, as well as reservist-volunteers, including many ex-naval men. The reservists were mustered into naval brigades, in which the training was geared towards coastal defence by sailors capable of ship handling and fighting as soldiers.

When the first Australian contingents, mostly from New South Wales and Victoria, sailed on 8 August 1900, troops from eight other nations were already engaged in China. On arrival they were quartered in Tientsin and immediately ordered to provide 300 men to help capture the Chinese forts at Pei Tang overlooking the inland rail route. They became part of a force made up of 8,000 troops from Russia, Germany, Austria, British India, and China serving under British officers. The Australians traveled apart from the main body of troops and by the time they arrived at Pei Tang the battle was already over.

The first Australian to die in China was buried on 6th October 1900. He was Private T.J. Rogers of the NSW Marine Light Infantry.

In total 556 Australians served in the Boxer Rebellion. Six Australians died of sickness and injury including Staff Surgeon J. Steel.